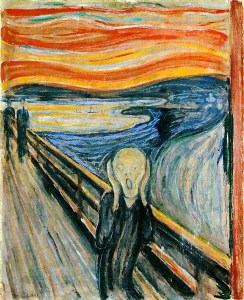

Expressionism is a style of painting, music, or drama in which the artist or writer expresses an inner emotional response rather than merely depicting an external reality. A deliberately exaggerated or altered rendition of reality allows the portrayal of subjective inner feelings. As an art movement, it was popular in Germany early in the 20th century. Edvard Munch’s familiar painting, ‘The Scream,’ was a precursor to the movement and the renowned canvas gives some idea of the technique.

Edvard Munch’s famous painting, The Scream, gives some idea of the emotional expressionist technique. (Image: public domain)

The German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder provided expressionism with a powerful new philosophical underpinning. This was the idea that self-expression is a primal need of human beings. Moreover, unless they cripple themselves with inhibition or self-constraint, whatever a person does expresses their whole nature. A new attitude toward works of art themselves arises from the view that an artist reveals himself in what he does. Philosopher and historian Isaiah Berlin has pointed out that, prior to the advent of expressionism, works of art were valued primarily as objects. Their value had nothing to do with the artist who made them or why they had come into being. In fact, for most people today, this view of art objects still prevails. Herder believed that, since a work of art is an expression of the whole being of the artist, including his cultural identity, it must be valued within that larger frame.

It is important to know that Herder advocated intuition over reason and carefully described reason’s limitations, his purpose being to reduce rational limits on intuition. Herder’s philosophy is still active. As one example, compare the idea of inhibition or self-constraint (above) with American SF writer Gene Wolfe’s notion that rejecting a memory of an experience because it violates the Western scientific paradigm constitutes “self-distortion.” Like Herder, Wolfe wants to sideline reason and unleash intuition or subjective knowing.

Ideas often evolve in a causal sequence. They develop and branch over time, one idea giving rise to another similar idea. Herder’s expressionism sounds a lot like an early version of existentialism. Expressionism stays within the confines of art and maintains that the work reveals the artist. The existentialists take a far broader view and say simply, “We are what we do.” Often linked with this creed is a Herder-like attempt to deny rational limits. Consider French existentialist philosopher Jean Paul Sartre’s militant refusal to believe in anything (including the unconscious mind) which might infringe upon his personal “freedom.” The withholding of belief is his denial of any logical restraints – however legitimate they may be in the eyes of others – on his ideas and behaviour. Sartre and Herder both wanted to believe only what they found convenient or expedient. Thus, expressionism and existentialism come to resemble egotism.

Expressionism as a philosophy established art as a manifestation of the artist as a person. It instituted art as a form of communication between creators and those who appreciate their work. By extension, any object made by human hands is in some way the expression of the worldview, conscious or unconscious, of its maker. If this matters, then creators have been elevated to a new level of importance in the scheme of things. Their worldviews are superior, worthy of admiration and adoption. Creators do not just make art objects or other kinds of artifacts; they enlighten others with their personal insights.

I have argued as much throughout this blog.

“It instituted art as a form of communication between creators and those who appreciate their work.”

And often those who don’t. I found this interesting as I had never thought of it as communication between, but rather as one-way communication.

Jean, you make a good point about those who do not appreciate a particular creator’s work. In fact, these people are often especially eager to send something (unkind!) back to the artist. This is the new reality of being creative, but I think most creators recognize the utility in having a variety of responses to what they are doing. Negative “feedback” still smarts, though.

Fascinating post, Thomas. But Sartre’s involvement in the French Resistance, while doing him much credit, doesn’t seem to square with his abstract philosophy, though I find it so complex that I have never been able to understand its application to personal behaviour….

Sartre talked a good resistance. Lucinda, but in reality he had little to do with it. Albert Camus, who was more seriously involved, became frustrated with Sartre’s self-aggrandizement, and said he was not a resister who wrote but a writer who resisted. Even that was being generous. (Camus was a very moral and decent man.) Sartre’s baloney still stands his reputation in good stead, though.

As for Sartre’s philosophy being abstract, I could not agree more. I once tried to read his Being and Nothingness, but had to stop after a hundred pages or so to save my skull from splitting! He wrote the Roads to Freedom trilogy to present his existentialist ideas in a more accessible way, but after reading all three semi-autobiographical books you get little sense of anything other than that Sartre knew bohemian Paris well, was a literary type, and a devout communist. He does manage to convey the idea of immersing yourself in life, participating in something you find meaningful, rather than remaining aloof and on the sidelines – which writers often tend to do. This is the most basic idea behind existentialism: you are what you do.

Sartre originally planned four books in the series, but gave up the effort after the third flopped badly. He wrote it in what can only be described as a ‘communist’ style. No paragraph breaks! All text is equal. It is truly a tiresome thing to read. The first two books are quite enjoyable, if you like reading about creative people and how they live their lives.

Personally, I think Sartre’s better at philosophical literature. I thoroughly enjoyed Nausea, and while I do think he is an interesting philosophical essayist, I wouldn’t say he stands against so many other philosophers. Gotta love him, though. Simone de Beauvoir is my favorite of the two. : )

I like Nausea too, although I don’t agree with all of the ideas in the novel. I have a big beef with Sartre. I think he goes too far in his attempts to liberate humans from limitations. He does not differentiate between the outside physical world and the inside psychological world. His argument that we can place our own subjective meaning on the world is fine (up to a point), but his claim that the unconscious does not exist because such a thing would infringe on his freedom is ridiculous egotistical nonsense.

I’m not fond of either Sartre or de Beauvoir, although they are interesting to study. As communists, they were both aware of Stalin’s huge massacres in the Soviet Union, yet deliberately said nothing for fear that confirming the rumours would damage the socialist movement in Europe. De Beauvoir taught her students to skip having children at a time when the French government was trying to get the birthrate up. (In those pre-socialist pre-feminist days, governments understood the importance of a survival birthrate.) During the early months of the Second World War, Sartre and de Beauvoir often flouted quite reasonable French regulations aimed at preserving national security. They were a pair of selfish, self-centred egotists who felt that all rules or regulations were a personal insult. That such people managed to admire a political system like that in the Soviet Union is troubling. Let me recommend Daniel J. Flynn’s book, Intellectual Morons: How Ideology Makes Smart People Fall for Stupid Ideas. Flynn explains all.

Haha, I think you’re right exactly. They were both very arrogant and put themselves in the class of intellectual superiority and remained in their ivory towers. I don’t disagree, but I do think they made a show. That’s particularly why I like absurdism (not that sartre or de beauvoir). Whimsical and flashy for the sake of flash and whim.