Romantics like to think of themselves as unique individuals who have the strength of character to go against the flow. They describe anyone who stays in the mainstream as a “conformist,” a word with negative connotations.

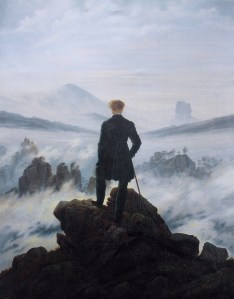

Romanticism promotes an anti-social emphasis on individuality and self-absorption. (photo: public domain)

Academic and novelist Ann Swinfen has some interesting things to say about this topic as it relates to C. S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia. In her work of literary criticism, In Defence of Fantasy (1984), she points out that Lewis was against individualism and in favour of conforming to religious orthodoxy and societal norms. His fiction reflects this strongly held rational philosophy.

Swinfen writes, “The repression of self in order to conform to an external pattern is an idea generally distasteful to post-Reformation man, but Lewis makes this theme more palatable by the stress he places in his fiction – as he felt it had occurred in his life – on the theme of ‘joy’.“

Furthermore, in his account of his religious conversion, Surprised by Joy, Lewis openly rejects introversion and introspection, the primary tools needed for cultivating individuality.

The truth is, of course, that the overwhelming majority of humans are always conformists. If individuality is in vogue, then people add pretending to be an individual to their false personas. Many will manage to convince themselves they really are individuals, usually without the faintest notion of what that means. This is to say, people don a make-believe mantle of individuality (deliberately doing and saying meaningless quirky things) in an attempt to conform to that notion’s current popularity. Romanticism is popular these days so, of course, many people have added being a romantic to their false personas as well.

The real issue goes deeper than just conformity versus non-conformity. Also important is whether the individual places personal concerns before or after the concerns of society as a whole. Ignoring the needs of society in favour of looking after one’s own needs – as recommended by the romantic worldview – does not qualify as refusing to conform to an “external pattern” if everyone else is doing the same selfish and destructive thing!

American professor of English Literature, Morse Peckham, has explored Romanticism’s anti-social attitude. He makes a crucial distinction between self (who we really are) and role (a part we play) pointing out that non-conformity got its start with Romanticism’s concept of what he calls the “anti-role.” The Romantics created a role deliberately counter to that of persons in mainstream society. Their aim was to differentiate themselves by taking up a role in favour of primitive nature instead of adopting the mainstream role that prefers manmade civilization. The anti-role also favoured imagination and emotion over reason. Romantics later improperly identified this anti-role as the self. In other words, only romantic non-conformists could claim they had a self. Only romantic non-conformists were individuals.

As desirable as this exclusivity may sound to those with romantic inclinations, to say a role is counter to that of mainstream society is just another way of saying the role is a form of alienation. Since we all grow up in mainstream society and are shaped by it, and since humans are, as a species, social creatures, to become alienated from mainstream society is, ultimately, to become self-alienated as well.

The truth is we are all individuals. Romanticism’s claim of exclusivity is false. Each of us has an authentic self made up of a unique set of emotionally important ideas formed when we were children. Many of us do not know this. Many of those who do know the truth fear to find out who they really are. However, the point here is this: when it comes to discovering the real person, conforming to the popular romantic anti-role is just as self-defeating as conforming to the mainstream role.

Related articles

- Reason and Emotion Clash in the Arts (thomascotterill.wordpress.com)

Thought-provoking as always, Thomas. The romantic individualist, always seeking to emphasise his or her difference from the mainstream, pretty much describes what I used to be like, and still am like in many ways. The ideal is seductive, after all, because it’s so – well, romantic.

Now I think that we are all, simply, individuals whether we’re romantics or not. There’s no need to cultivate a deliberate attitude of otherness – we just are ‘other’, inescapably so. Moreover, I sometimes doubt that words such as ‘conventional’ and ‘unconventional’ really signify anything at all in a world where values have fragmented to such a degree.

Such are my rational thoughts, at least. Part of me will always be an unreformed romantic, I’m afraid … 🙂

Since romanticism is still so prevalent in the West, it is entirely possible – likely even – that many of us develop some genuine romantic attitudes and values as youngsters. The part of you that remains stubbornly romantic may well be quite authentic, Mari. The trick is to weed out any artificial elaboration you might have added to what is already there. You cannot usefully work with your romantic personality elements unless you find the real ones. As you say, conscious adherents of romanticism or individualism are always looking to emphasize their differences so they can enhance their false presentation of themselves as special individuals. This is ego trying to dominate again rather than accepting the self as it stands.

I like what you said about conventional and unconventional having little meaning in a fragmented world. This is so true. Here is a question to consider. How fragmented would the world be if we were all more authentic? We would all be individuals, but the differences would be subtle, genuine, and reflect social realities. Forging larger cohesive social groupings would be much easier. In other words, well integrated individuals would yield well integrated societies.

Perhaps the ultimate freedom would be a collective effort of awareness in which people freely join together to playfully re-imagine the world, each integrating personal flavor, talents, and voice. Since reality is but the sum of our collective imagination, why not make that process of imagination conscious and purposeful? This is probably a romantic vision of the potential of reality, but I do believe it is also realistic, in that imagination produces the real.

What you suggest sounds lovely, Merma. I’m a realist, so I believe imagination can directly produce reality only in the subjective sense that it colours how each of us sees and experiences the real world. However, I do think imagination influences the ideas, innovation, and actions that make the world what it is.

“The truth is we are all individuals. Romanticism’s claim of exclusivity is false.”

“Romanticism” didn’t make any claims at all. Least of all that one. As a common thread Romantics (in the real 18th century sense) were rediscovering a way of being in the world that had more depth than Enlightenment rationalism, without it being a prerequisite that they thereby become irrational.

Isaac, I cannot agree with you that the original Romantic Movement made no claims. Beyond the poets, painters, and writers who stressed individuality and self-expression, the movement also had a philosophical component in thinkers such as Schiller (who was also a playwright) and Hegel. All these participants did indeed make claims – some very big ones, in fact. For example, Schiller asserted that the individual achieved moral greatness (became heroic) by overcoming shared instinct and human feeling. As another of my posts illustrates, he made a heroine of Medea for boiling her children alive! Liberation of the human spirit required rising above natural constraints and ordinariness. Hegel gave us a formulation of the dialectic, and the romantic notion of the nation state as a “volk” or people. He advocated a unified Germany with a strong national spirit claiming it was Germany’s natural role to counterbalance proudly rational France.

I do agree that Romanticism was a reaction against the excessive rationalism of the late Enlightenment. Goethe’s Faust (a favourite of mine) is a model for the rejection of dry intellectualism in favour of a more passionate lifestyle and greater engagement with the world. The movement’s emphasis on emotion, by definition irrational, is the source of the idea that Romanticism championed irrationality. However, it is true that, leaving out high emotion, one does not have to become irrational to stand against an excess of reason.

Romanticism as an art movement ended after a few decades, but the core ideas have lived on. My assertion that romanticism makes an exclusive claim on individuality stems partly from my own experience with romantic types and partly from the work of students of romanticism such as Jacques Barzun, Morse Peckham, and Isaiah Berlin. Peckham especially does an excellent job of defining the romantic’s conception of him- or herself as someone uniquely opposed to the mainstream culture. Everyone else is a conformist.