Many famous writers have used the people in their lives as grist for the authorial mill. The spicy roman à clef has long been a frequent visitor to bookshop shelves. Even more common are realistic novels based on the lives of actual people, but where no deliberate effort is made to link with the objects of inspiration. In other words, the real people are convenient sources of material, yet too obscure to be of interest to the reading public. The writer’s own life may also end up on the page. If his own experiences predominate, a struggle with illness, say, we call these works autobiographical novels, but in many cases, the lives of people around the writer are also included and the situation becomes less clear-cut.

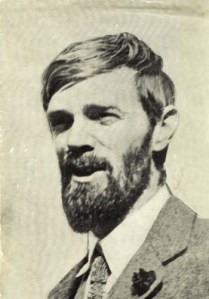

D. H. Lawrence was notorious for using lovers, friends, and acquaintances as thinly disguised characters in his sexually explicit novels. (Photo: public domain)

Opinions vary as to the merits of drawing on real people for inspiration. The competing view is that characters are better created from imagination especially for the job of telling a particular story, highlighting some aspect of human nature, or revealing the human condition. The latter being that rather nebulous concept which “includes concerns such as the meaning of life, the search for gratification, the sense of curiosity, the inevitability of isolation, or awareness regarding the inescapability of death” (Wikipedia). A third position, which I am inclined to share, claims pure imagining is impossible.

H. G. Wells made heavy use of autobiographical material – and of real people and their lives – in his work. Even more famous for the habit was D. H. Lawrence, whom H. E. Bates roundly criticized for the practice. Bates claimed not to do this himself, and maintained that he depended instead on the more respectable method of imagination. But is this really the case? Having read Bates’ three-volume autobiography, I can see much of his own life in his work. For example, as a young man, he worked as a newspaper reporter, just like his character in Love for Lydia. It is probable that all writers of character novels draw on their own lives to one extent or another. It is hard to see how it could be otherwise. Some are better at disguising this than others, however. Writers like H. E. Bates probably make use of their own experience less consciously, and so it seems to them they are not being autobiographical when in fact they are.

While discussing H. G. Wells’ character, biographer Lovat Dickson writes, “[Wells] had, in fact, an expressed distaste for party politics and intrigue. It was what made him so irritable with the Fabians. This is a perfectly natural attitude for an artist. But he had the writer’s curiosity about personality.” Dickson makes the point that Wells is using real events and personalities in order to get closer to life in his books. There is nothing so real as reality, in other words.

Yet, as I have noted, others seem to disagree with what at first blush seems an unassailable position. Just as H. E. Bates placed heavy emphasis on imagination rather than stealing from the real world, Henry James criticized Wells’ use of the autobiographical form, “which puts a premium on the loose, the improvised, the cheap and easy.” In other words, real life does not necessarily do the best job of revealing character and exploring the realities of the human condition. Consciously contrived characters and situations can present insights more clearly. The dispute seems to centre on which has more impact: the portrayal of accurate but ambiguous reality or vivid character creation and storytelling designed to make a particular chosen impression.

A critic for the Calgary Herald touched on this issue in a review of Margaret Drabble’s The Gates of Ivory. “[The novel is a] tour de force for those of us who believe fiction can offer a reality and truth beyond that of non-fiction.” The statement raises an interesting question: Do imaginative writers of fiction have better perception and insight into human nature than writers who depend on real people, or is it the case, as I have suggested above, that contrived presentation simply allows easier visibility and interpretation.

Personally, I have long preferred biographies to character novels, and it is the bedrock feeling of reality of the former that appeals to me, along with the opportunity to make up my own mind about the significance of actions and events. Surely, fiction writers inspired by the character and lives of real people are able to provide some of the same benefits. The problem with imagined characters and situations, divorced as they are from the constraints of reality, is the greater risk of persuasion to the author’s own peculiar point of view; that is to say, of being inadvertently propagandized! On the other hand, there is always the touchstone of recognition when a writer’s insights ring true regardless of their origin.

Related articles

- Young H. G. Wells Exemplified the Struggling Writer (thomascotterill.wordpress.com)

- H. G. Wells’ Struggle with Sensuality (thomascotterill.wordpress.com)

Fascinating stuff, Thomas.

I wonder if our novels aren’t a bit like our dreams, coming from the unconscious as they do, with some recognisable traits from real people blended in with made up ones? I’ve forgotten the word for this. I remember yawning through ‘The Forsyte Saga’ which should have interested me, but didn’t, because Galsworthy just can’t portray Irene objectively, as he was so obsessed with his real life equivalent. I think he managed to change the hair colour, and imagined that was enough to put readers off the scent, ha, ha!

Interesting, as always. Seems to me that if you’re not writing motorcycle repair manuals, you’re writing about your life. Just be sure to change the names and add a moustache here and there.

An interesting post, Thomas. Individual authors do what is best for them, but personally I’m wary of the idea of straightforwardly using real people as characters. Of course, we all draw heavily on our own lives and experiences – we could hardly do otherwise – but, in my experience at least, characters are not created – they evolve. They gradually become real people to the author; you have to take time to get to know and understand them.

I often make use of a particular aspect of a real person as a handy starting-point – basic personality type, appearance, speech, and so on – but the end character is very different to the original model. Apart from anything, I doubt that you could ever know a real person as well as you can a purely imaginary one – a rather alarming thought, I suppose.

I too am wary of authors who use their works and characters for the purposes of propaganda, whether they do so consciously or unconsciously (though again, of course, the author’s personal views will inevitably make themselves known). However, a properly-imagined character can actually safeguard against this, I think. When characters become real, they often start thinking and behaving as they wish – and not necessarily as we would like them to!

Lucinda, I think you’re right about the unconscious and the way writers develop their characters. For many authors, the process is largely intuitive. They have a “feel” for what the story needs and what emerges is a complex mix of borrowed and imagined traits and behaviours.

At a more conscious level, I believe the process of character creation can cut both ways. A writer can start with an imaginary personality designed to carry a particular story, and then the unconscious gets involved. All sorts of other stuff, often drawn from the memory of real people, starts worming its way in, the goal being a more realistic and convincing portrayal. Or writers may use a real person as a suitable model, and then find themselves imagining all sorts of things about what this character might or might not do under the circumstances. In other words, the writer enhances or elaborates the original in new, often unexpected, directions.

Evan, I agree that a lot of serious writing comes in some way from the writer’s own life. What emerges may be lightly or heavily disguised, but it is the actual experience behind the work that provides the vital sense of authenticity and relevance. Hemingway would be a good American example here.

Having said that, we must not forget the moralizing novels that have always been popular with lovers of literature. These arise from the author’s sense of right and wrong, or from an attempt to explore what is right and wrong in situations where there is much ambiguity. Often based on careful research, these works have more to do with philosophical thinking about values than with physical experience, although one might powerfully argue that they reflect the *inner life* of the writer.

Thomas Mann’s classic, *The Magic Mountain* is an excellent example of this kind of writing. Mann spent all of 30 minutes in a Swiss tuberculosis sanatorium and wrote his huge novel based on a quick glance into the dining hall and a few words with a patient and some staff. The long fascinating conversations among the patients are staged to reveal Mann’s understanding of the key philosophical questions of his time.

Mari, I was hoping you would chime in here. You are one of those writers with a growing clarity about her process and I always enjoy getting your coherently expressed perspective.

I think using real people as characters comes with the limitation that doing so depends on also using their real life experiences. After all, actual behaviour is how we come to know people. If the demands of a story go beyond what we know about our characters, then we must speculate and what was real rapidly becomes imaginary or fictitious.

That characters evolve is something with which I agree completely. I often suggest there is no need to worry about “cookie cutter” characters for the simple reason that, however they may start off, characters are definitely not going to stay that way! The demands of the story and the writer’s growing “feel” for its characters inevitably entail an expansion in sophistication and subtlety. Fiction would be much diminished if this were not the case.

I think, your remark about characters acquiring a life of their own relates to Lucinda’s observation on the influence of the unconscious mind. When a character gets “out of line,” you can bet your unconscious is racing ahead of consciousness in working out the ramifications of your story. Since unruly characters can mean massive changes, I try to tame mine by spending a lot of time at the outline stage. In other words, I get to know my characters more thoroughly before I start the first draft. This does have the intended effect of reducing the need to rewrite, but whether I pay a price in terms of the quality of my characterizations, I cannot say.